Of all the criticisms you could make of my work, the one I’m most sensitive to is “There’s nothing going on here. Nothing is happening.”

When I was a young writer, I developed a lot of good writing habits. I learned not to censor myself. I learned to write on the spot. I learned patience and discipline, to let the work unfold on its own time.

What I didn’t learn was how to write something that wasn’t boring. My finished drafts would eventually arrive at something readable, but I didn’t have a framework or a set of techniques for making that happen in early drafts. It took me a long time to get there.

For lack of a better word, I’m talking about the ‘movement’ in work. What makes the work ‘move along.’ There is no single way to create, for lack of a better word, the ‘momenutm’ that keeps a reader reading. But there are some ways to practice what it ‘feels’ like to generate that momentum.

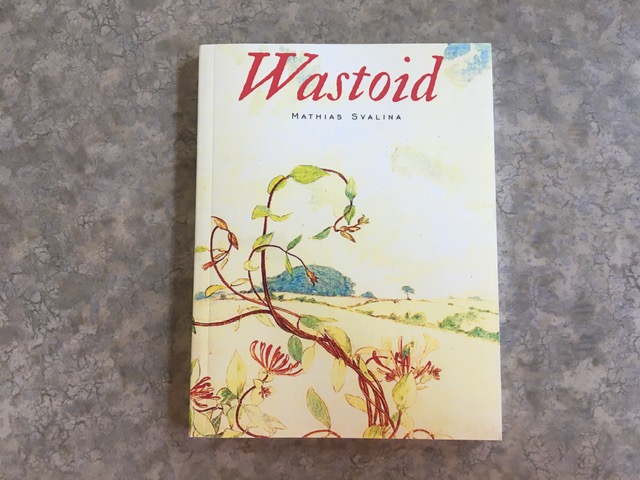

One way is to make use of conjunctions and transition words like ‘then.’ I was inspired to codify this into a writing exercise after reading Mathias Svalina’s Waistoid. A lot of writers bend genres; Svalina blends them, and in ways that make the whole greater than the sum of its parts.

The poems in Waistod are characterized by the overt presence of ‘momentum’ and ‘movement.’ You cannot start reading one of them without being pulled through to the end. Technically speaking, he makes this possible with ‘and,’ ‘but,’ ‘then,’ ‘when,’ ‘then’ and other markers. (He also uses repetition and other rhetorical techniques, but this exercises is inspired by his use of conjunctions.)

Here’s an example. I’ve bold-faced the words I think contribute to the poem’s ‘movement’:

My lover tries to trip the man in the tollbooth but the man in the tollbooth is a grandfather clock. The setting sun withers the flowers away & my lover collects each dried petal in a tiny glass vial. The grandfather clock in the tollbooth has stopped ticking & begun a long, low groan. Every noise is made against a backdrop of noise. Death is irrelevant: each car passes the tollbooth & leaves its dollar on the scratched steel shelf.

Obviously, there is so much else going on in this poem and the rest of the book, but I think there’s a lesson to be learned about how some rhetorical effects are generated by technique. So I offer this writing exercise as a way to help you experience a sense of ‘movement’ in your writing, especially in first drafts, when nothing apparent might be going on.

The Writing Exercise

- Begin with the sentence: My lover broke up with me on a Thursday.”

- Start the next sentence with “And …”

- Start the sentence after that with “But…”

- Start next sentence with “Then …”

- Keep writing, alternating “And, But, Then” sentences until you are exhausted.

###