This is from a project I work on sporadically, a series of “Spiritual Labyrinths” inspired by the Gestlicher Irrgartens that were popular with the Pennsylvania Dutch. I grew up in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, so the material culture there is something that I took for granted until I moved away.

For a great introduction to traditional Spiritual Labyrinths, I suggest downloading Perplexion and pleasure: the Geistlicher Irrgarten broadsides in the German-American printshop, home, and mind by Trevor Brandt. The appendices include a great catalog of various examples of the Spiritual Labyrinths, plus translations so you get an idea of how the text, design, and physicality of the broadsides interact.

The traditional broadsides are just one point of departure for my project, which also draws inspiration from the concrete poetry movement, Oulipo and their aleatoric writing methods, neurology, and direct mail marketing, among other areas.

Some Words about My Method

This is a project I work on when I don’t feel like working on anything else, especially when I tire of words by themselves. It’s pure play. I never get caught up in trying to make these labyrinths ‘good,’ and they’re all quite sloppy as a result.

I star with canvas and some thin painter’s tape. I’ll make the patterns with the tape, usually while I’m watching TV. It’s a meditative process of laying down tape into a pattern, then peeling it off when I don’t like the result. If I’m happy with the pattern, then I’ll usually throw a coat of paint over it. When it’s dry, I peel off the tape and it leaves the pattern behind, the ‘labyrinth.’

I generate the text two ways. For most of the labyrinths, I cut phrases from an old dictionary. I piece together scraps into fragments and sentences that sound good to me. I glue them onto the canvas.

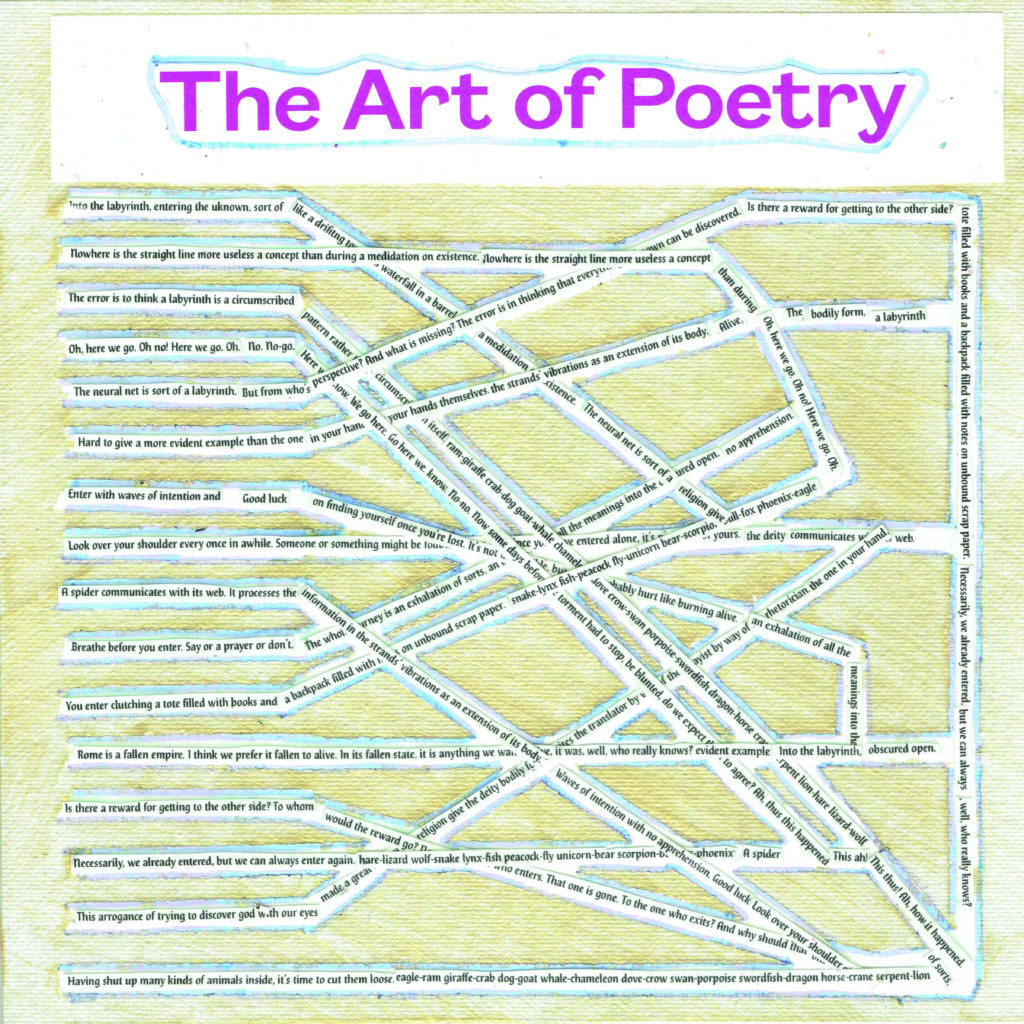

The other method is that I will write the langauge myself. In “The ARt of Poetry No. 1” (pictured), I wrote a series of sentences, chose the ones I liked most, then printed them on cardstock. I cut them out and glued them to the canvase. It’s hard to appreciate in the photo, but the places where language overlaps are rough and thick. All the text is slightly raised, but at those intersections, there are small mounds. The haptic quality of the physical object is an important part of its aesthetic appeal. To look at this image is one thing, but to hold it in your hand and feel the canvas and see the raised words is another.

Traditional spiritual labyrinths were not only held, they were turned around and around as the reader worked through the story or prayer. So engaging with a spiritual labyrinth was a physical activity, involving not only touch but motion and movement. That’s one of my favorite things about the finished pieces that I’m workign on. It’s nothing like reading a poem from a book, where the words are static and the most activity that’s involved is turning the page. Here is an form of reading that’s dynamic and overtly physical.